Thanks to Brad – the subscriber who brought this story to our attention. If you have a story idea feel free to contact us directly: ask@morethanjustparks.com.

There’s a kind of forest in western Oregon that you feel before you understand. The canopy closes overhead and the light changes. The air goes cool and wet and still. Old-growth douglas fir and western red cedar rise two hundred feet, draped in moss so thick the trunks disappear beneath it. The forest floor is fern and lichen and fallen giants slowly becoming soil. You can stand in these places and feel, viscerally, that you’re inside something alive. Something that was functioning long before anyone thought to measure it and will outlast whatever we decide to do with it.

If we let it.

On February 19th, the BLM published a Notice of Intent to gut the management plans governing nearly 2.5 million acres of these forests across 18 counties. The proposal seeks to eliminate old-growth and wildlife protections to facilitate what the agency calls “maximum” logging capacity. The stated goal is to accelerate timber harvest to approximately one billion board feet per year. That’s four times current levels. It would match the peak production of the 1960s, before the Endangered Species Act existed, before anyone with authority cared whether a spotted owl or a salmon run survived the next decade.

The existing management plans were finalized in 2016. They took four years to develop. They balanced timber production with habitat protection, water quality, recreation, and the survival of species that federal law requires us to protect.

The administration wants to tear them up. And they’ve given you 30 days to say something about it.

There will be no public meetings.

The agency charged with managing one in every ten acres of land in the United States wants to fundamentally reshape how some of the most ecologically significant forests in the world are managed. And they don’t intend to look a single person in the eye while they do it.

Upgrade to Paid

These are some of the last remaining low-elevation old-growth forests in Oregon. They store more carbon per acre than any terrestrial ecosystem on the planet. They filter drinking water for downstream communities. They hold soil on steep slopes above salmon streams that are already in crisis. They’re home to the northern spotted owl, the marbled murrelet, coho salmon, steelhead, and hundreds of species that evolved over millennia in conditions you can’t replicate by planting seedlings in rows.

The places directly threatened by this proposal have names. The Valley of the Giants. The Sandy River corridor. The North Fork Clackamas. Mary’s Peak. Crabtree Valley. Alsea Falls. The Upper Molalla River. These aren’t abstractions on a planning map. They’re places people hike, fish, paddle, and come back to year after year. They’re places that remind us we belong to something older than ourselves, that we’re capable, as a country, of deciding some things are worth more standing than cut down.

Now the Trump Administration wants to open them all up for destruction.

We’ve been watching this assemble itself for months. An oil billionaire running the Interior Department who calls extractive industries his “customer.” A BLM nominee who’s publicly denounced Theodore Roosevelt for protecting land. A timber executive running the Forest Service. A corporate concessionaire tapped to lead the National Park Service. Every agency handed to someone whose career was built on opposing that agency’s mission.

You don’t install that lineup for reform. You install it for liquidation.

And this Notice of Intent is yet another one the invoices.

If you’re not familiar with the O&C lands, here’s the short version. In the early 1900s, the federal government granted millions of acres in western Oregon to the Oregon and California Railroad to encourage settlement. The railroad violated the terms of its grants by hoarding rather than selling the land. Congress revoked the grants in 1916, and in 1937 passed the O&C Act, which placed roughly 2.5 million acres of these revested lands under the Department of the Interior.

The O&C Act directed the BLM to manage these lands for sustained-yield timber production. Timber receipts were shared with the 18 counties where the lands are located, and for decades that money funded schools, roads, law enforcement, and basic services. Through the 1960s and 70s, annual harvests routinely exceeded one billion board feet. The peak came in 1964 at approximately 1.6 billion board feet. It was an era of aggressive, industrial-scale logging with virtually no environmental guardrails.

Then the science caught up. The northern spotted owl was listed as threatened in 1990. The marbled murrelet followed in 1992. The Northwest Forest Plan arrived in 1994. Harvests plummeted from over 700 million board feet in 1990 to under 100 million by 1994. County timber receipts collapsed from $109 million in 1989 to $21 million by 1995. Communities that had built their entire economies around timber were devastated.

That pain was real and shouldn’t be dismissed. Congress responded with safety net payments and the Secure Rural Schools Act, which peaked at $116 million in 2006 before declining steadily. Recent payments have hovered around $25-30 million. The 2016 Resource Management Plans attempted to strike a balance, allocating about 20 percent of O&C forestland for sustained-yield harvest while maintaining habitat protections for listed species. Last year, O&C lands produced about 267 million board feet and generated $66 million in timber receipts.

The timber industry and the Association of O&C Counties argue this isn’t nearly enough. They say the BLM is only harvesting a fraction of annual growth and violating the O&C Act’s sustained-yield mandate. They argue the forests are overstocked, fire-prone, and that increased logging would reduce wildfire risk while reviving county budgets and creating thousands of jobs.

That argument deserves a serious response. And here it is.

The BLM’s own prior analyses have acknowledged that industrial clearcutting and plantation management increase fire risk. Conservation groups have been pointing this out for years. A forest scientist at Oregon State University called the plan insanity, noting that these are the most effective carbon-storing forests in the world, as long as they remain intact.

Wildfire management has been used as a trojan horse by this administration and its allies in congress. It’s well known that industrial clearcutting followed by dense plantation replanting creates exactly the kind of fuel-loaded, fire-prone landscape the agency claims to be worried about. The BLM knows this. They’ve said as much in their own documents.

The proposal also calls for shrinking streamside logging buffers to as little as 25 feet. That’s not a typo. Twenty-five feet. For context, the science on protecting endangered fish like coho salmon and steelhead has consistently shown that buffers of that size are nowhere close to adequate for maintaining water temperature, preventing sediment runoff, and preserving the habitat these species need to survive.

And there’s the legal track record. Courts have repeatedly sided with conservation groups in recent years, finding that even under the significantly weakened 2016 plans, the BLM regularly violated its own rules and bedrock environmental laws to push through commercial logging projects. In one case, the agency was accused by its own former employees of fabricating analysis to justify more aggressive cuts.

That’s the agency asking for more authority. That’s the agency saying trust us with fewer guardrails.

The language tells you everything about intent. The BLM frames the entire revision as a return to the O&C Act of 1937, treating reduced harvest levels over the past three decades as a policy failure rather than the result of science, litigation, and the plain reality that you can’t clearcut old-growth habitat and expect threatened species to survive. Two Trump executive orders we wrote about on expanding timber production are cited as justification.

The stated purpose is to seek “sustained yield of timber harvest that aligns with the historically higher levels of production.”

Historically higher levels. That’s bureaucratic language for a simple ambition – go back to a time when none of these protections existed, when the only metric that mattered was volume.

The notice identifies only two alternatives: do nothing, or manage for “maximum productive capacity.” That’s the range. The full spectrum of options being considered runs from the status quo to full industrial logging. There’s no middle ground alternative. No alternative that updates the science while modestly increasing harvest. The BLM has told you where it wants to end up.

The interdisciplinary team listed in the notice is also revealing. Forest management, fuels, GIS, fisheries, and wildlife. No recreation specialist. No hydrologist. No climate scientist. For a plan governing 2.5 million acres that directly impacts drinking water, salmon habitat, carbon storage, and outdoor recreation, that’s a pretty conspicuous set of omissions.

The scoping comment period closes March 23, 2026. This is your window. Scoping comments shape the alternatives the BLM is required to analyze in its Environmental Impact Statement. If enough people demand that the agency consider alternatives that balance timber production with conservation, habitat protection, clean water, recreation, and climate, they’ll have a much harder time pretending those concerns don’t exist when this ends up in court. And it will end up in court.

Submit a comment. You can do it right now:

Online: ePlanning project page — click “Participate Now”

Email: <a href="mailto:BLM_OR_Revision_Scoping@blm.gov">BLM_OR_Revision_Scoping@blm.gov</a>

Mail: Bureau of Land Management Oregon/Washington State Office, 1220 SW 3rd Avenue, Portland, OR 97204, Attn: Elizabeth Burghard, RMP Revision

What to say. You don’t need to be an expert. You don’t need to write a legal brief. A few sentences in your own words carry weight. But if you want to make your comment as effective as possible, here are the points that matter most:

Demand additional alternatives. The BLM has only proposed two: do nothing or maximize logging. Insist they analyze alternatives that increase harvest modestly while maintaining meaningful protections for old-growth, listed species, water quality, and recreation.

Challenge the fire argument. The BLM claims increased logging will reduce wildfire risk. The science says the opposite for industrial clearcutting and plantation management. Say so.

Raise the streamside buffers. Twenty-five-foot buffers are a joke for protecting endangered salmon and steelhead. The agency knows this. Call it out.

Defend the ACECs. The BLM is required to reevaluate all existing Areas of Critical Environmental Concern in the planning area. That’s over 100 designated areas. If you’ve visited any of them, say so. If they matter to you, say so.

Name the places you care about. Valley of the Giants. Mary’s Peak. Alsea Falls. The Sandy River. The North Fork Clackamas. The Upper Molalla. Personal connections to specific places carry real weight in NEPA proceedings.

Demand public meetings. The BLM has said it doesn’t intend to hold any. That’s unacceptable for a decision of this magnitude. Tell them.

Share this piece. The comment period is 30 days. Most people have no idea this is happening. The more people who know, the harder it is to push through quietly.

Get out there and raise hell.

Until next time,

Will

Leave a comment

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

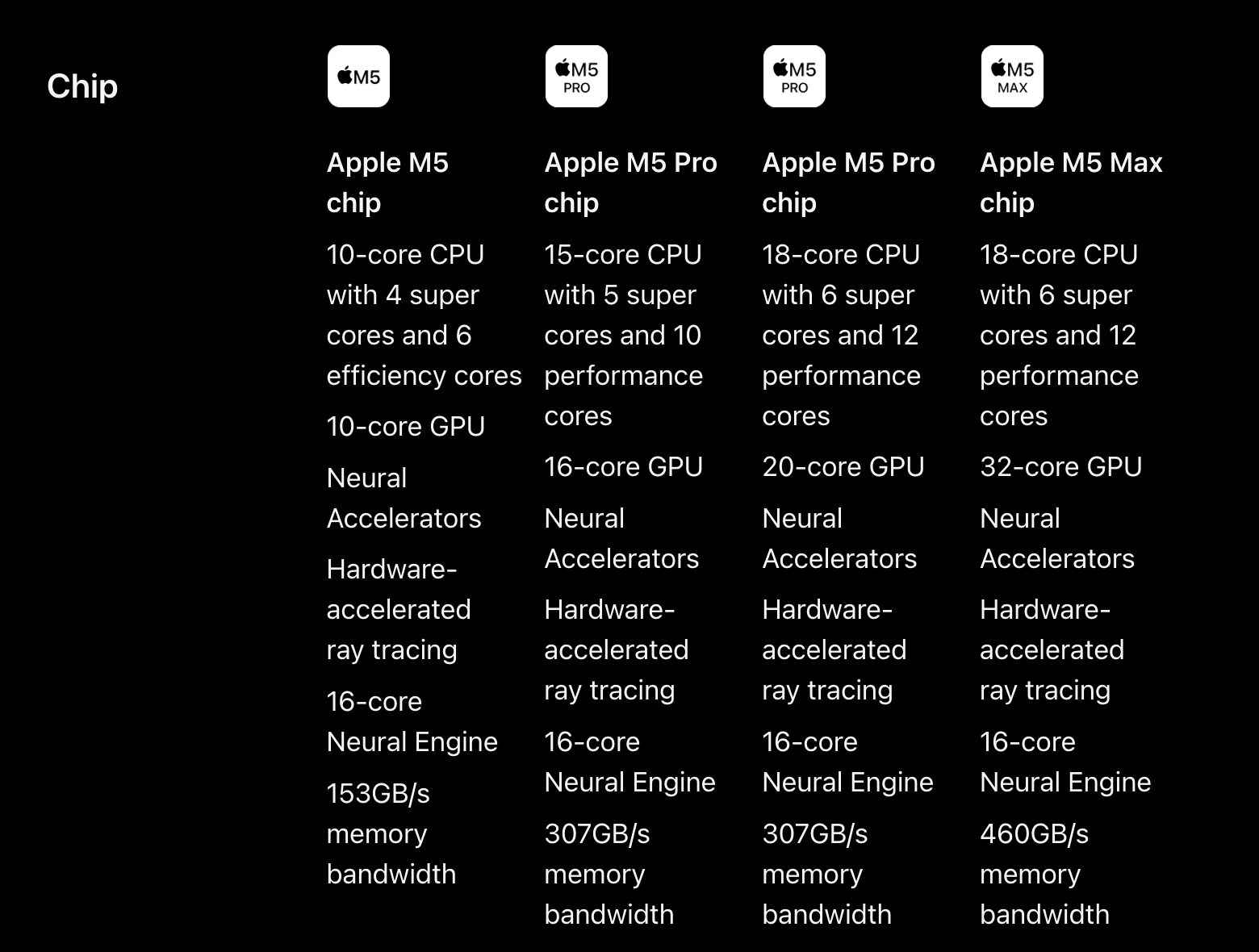

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple