WESTLAKE VILLAGE, Calif.—When the Chevrolet Bolt debuted in 2017, the electric hatchback stood out: Here was an electric vehicle with more than 200 miles of range for less than half the price of a Tesla Model S. The Bolt had its ups and downs, though. A $1.8 billion recall saw the automaker replace the battery packs in more than 142,000 cars, which wasn't great. COVID delayed the Bolt's midlife refresh a little. It got a price cut—the first of several—plus new seats, infotainment, and even the Super Cruise driver assist, plus a slightly more capacious version called the Bolt EUV.

Along the way, the Bolt became GM's bestselling EV by quite some margin, even as the OEM introduced its new range of more advanced EVs using the platform formerly known as Ultium. But as is often the way with General Motors, a desire to do something else with the Bolt's assembly plant saw the car's cancellation, as GM wanted to retool the Orion Township factory as part of its ill-judged bet that American consumers would embrace full-size electric pickups like the Silverado EV. And thus, in 2022, GM CEO Mary Barra announced the Bolt's impending demise.

This was not well-received. Even though Chevy promised an almost-as-cheap Equinox EV, Bolt fans besieged the company and engineered a volte face. At CES in 2023, Barra revealed the Bolt would be brought back, with an all-new lithium iron phosphate battery in place of the previous lithium-ion pack. When GM originally designed the Bolt, it was the company's sole EV, but now there's an entire (not-) Ultium model range. The automaker also has a giant parts bin to pick from, so the Equinox EV donates its drive motor, plus there's a new Android Automotive OS infotainment system.

But you could have read all that ages ago. Chevy announced some specs and pricing last October, including the news that there would be a sportier RS trim in addition to the LT version. Then, in January, we learned its 262-mile (422 km) range and the fact that it can DC fast-charge at up to 150 kW, using a NACS socket instead of CCS1. Now, we've had a chance to spend some time behind the wheel of the 2027 Bolt, and here's what we found.

Spec sheets can be misleading

As before, the Bolt's electric motor drives its front wheels. The drive unit generates 210 hp (157 kW), a 4 percent bump on the old car. But its torque output is just 169 lb-ft (230 Nm), well down on the 266 lb-ft (360 Nm) of the earlier Bolts. This had me worried: near-instant and effortless torque practically defines the EV driving experience, and the thought of missing nearly 40 percent of that thrust sounded like it would make for a radically different driving experience.

In fact, the 2027 Bolt is actually slightly zippier than the old car. The motor's torque output might be less, but with an 11:59:1 final drive ratio, you would never, ever guess. Zero to 60 mph (97 km/h) takes 6.8 seconds, 0.2 faster than before. The new motor can spin faster than the old one, and so even at highway speed there's sufficient acceleration when you need it.

The new powertrain is also more efficient. Even though much of our drive route was on challenging—and hilly—roads like Mulholland Drive down to Malibu, and mostly in Sport mode, I still saw around 4 miles/kWh (15.5 kWh/100 km). So that 262 mile range estimate from the 65 kWh battery pack sounds spot-on.

Perhaps the old Bolt's biggest weakness was how slow its DC charging was—almost an hour to 80 percent at a maximum of just 55 kW. Now with NACS, things are a lot better. I tested recharging a Bolt LT from 19–80 percent using a Tesla V4 Supercharger, which took 25 minutes and added an indicated 211 miles of range. The charge curve is much flatter than before, starting at ~110 kW before gradually beginning to ramp down once the state of charge passed 65 percent. Like other batteries, the LFP pack will charge much more slowly once it reaches 80 percent, but unlike lithium-ion, you're encouraged to charge the car to 100 percent as often as possible.

For most charging networks, recharging is as simple as plugging in and letting the car and charger talk to each other using plug and charge (ISO 15118); this is still being implemented for Tesla Superchargers, but you can initiate a charge from the Bolt's charging app. A word of caution though: The charge socket is on the driver's side of the car, which means you'll have difficulty using a V3 Supercharger—which only features a short cable—without blocking more than one stall, something that may enrage any Tesla owners hoping to charge simultaneously.

Fast-charging is actually fast now.

Credit:

Jonathan Gitlin

Fast-charging is actually fast now.

Credit:

Jonathan Gitlin

And before you ask, no, it wasn't possible to relocate the charge port; this would require a significant redesign to the car's unibody as well as its powertrain layout, at vast expense.

Drives like a Bolt should

Although the new $32,995 RS trim has a sportier appearance inside and out than the $28,995 LT, both trims use identical suspension tuning. The ride is more than a little bouncy over the expansion gaps of LA's highways, but a look at previous reviews reminds me that old Bolts also did this. The effect was much less noticeable on the back roads, where the car proved nimble if not exactly captivating to drive: I would very much like to try one on performance tires. The range would suffer a little, but cornering grip would be much improved. That said, the low-rolling resistance tires have more grip and are less likely to break traction than, say, the Toyota bZ we just reviewed.

There's a new power-steering actuator, and a new rear-twist axle, but the suspension and steering geometry should be the same as older Bolts.

However, if you're familiar with the old Bolt, you'll notice a few changes. The cabin has a lot more storage nooks and cubbies than before, and both the main instrument panel and the infotainment screen are larger than in a 2023 Bolt. You use a stalk mounted on the steering column to select D/R/N/P, and must now use a persistent icon on the touchscreen to toggle one-pedal driving on or off. This is less convenient than the old car and its physical controls. The regenerative braking paddle is gone from behind the steering wheel, too.

But there are two settings for one-pedal driving, one gentler than the other, and you'll also regenerate energy using the brake pedal. Exactly how much regen occurs before the friction brakes take over depends on things like the battery's state of charge; in high regen, I saw as much as 85 kW by lifting the throttle, and the same with one-pedal driving turned off but using the brake pedal to slow. With one-pedal turned off, the car will still regenerate a few kW when you lift the accelerator pedal, so, unlike a German EV, this car won't coast freely.

Is this the McRib of EVs?

Any worries that the rebatteried Bolt would be missing the car's essential character were misplaced. Although some of the numbers on paper look lower, the driving experience is no worse than the old car in most ways, and improved in terms of onboard safety systems, powertrain efficiency, and so on. The comments will no doubt reflect antipathy that GM dropped Apple CarPlay and Android Auto to cast one's phone, but the inclusion of apps like Apple Music might go some way toward alleviating this angst. In all, the 2027 Bolt represents a solid upgrade.

But there's a catch. Just like last time, GM has other designs on the Bolt's assembly plant—now in Fairfax, Kansas. That factory will churn out Bolts for just 18 months; next year production ends and the automaker repurposes the site to build gasoline-powered Buick Envisions and Chevy Equinoxes. Chevy told us that it expects there will be sufficient Bolts to stock dealerships for the next two years, but after that, it's done.

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

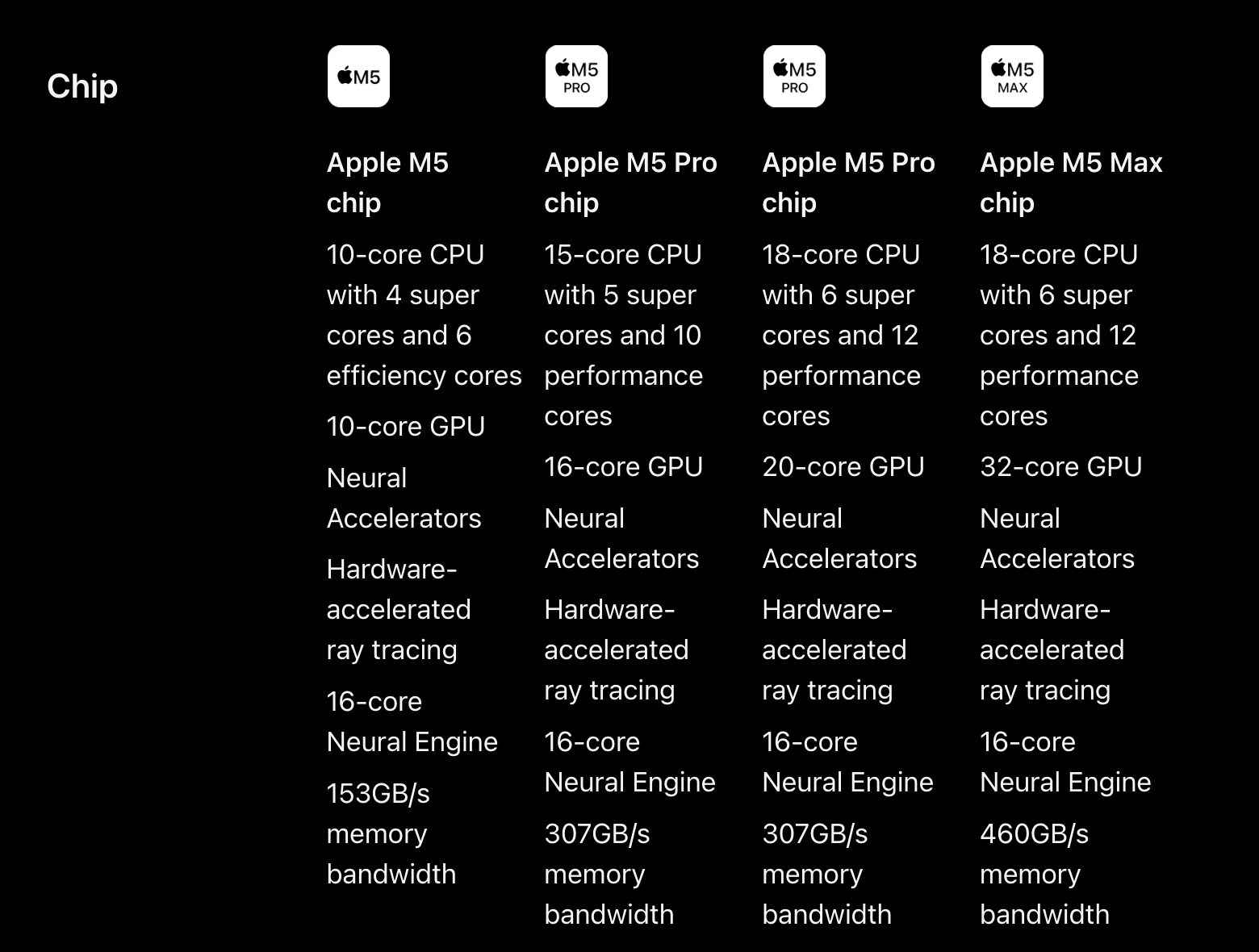

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple