The Spinosaurus is a sail-backed, crocodile-snouted dinosaur that Hollywood depicted as a giant terrestrial predator capable of taking down a T. rex in Jurassic Park 3. Then they changed their mind and made it a fully aquatic diver in Jurassic World Rebirth—a rendering that was more in line with the latest paleontological knowledge.

But now, deep in the Sahara Desert, a team of researchers led by Paul C. Sereno, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago, discovered new Spinosaurus fossils suggesting both scientists and filmmakers might have got it all wrong again. The Spinosaurus most likely wasn’t an aquatic diver because, apparently, it couldn’t dive.

Bones in the sand

While the T. rex-beating version of the Spinosaurus was considered unlikely due to its relatively fragile skull, the newer depiction as an aquatic diver made more sense in light of paleontological evidence. Until now, all remains of these predators were pulled from coastal deposits near ancient seas and oceans. That geographic distribution was consistent with the aquatic lifestyle interpretation. If a creature lived on the coast, maybe it swam out to sea like a prehistoric seal, only crawling out to the beaches to rest just as it was depicted in Jurassic World Rebirth.

But the Spinosaurus found by Sereno and his colleagues lived in a completely different neighborhood. The fossils were discovered in the central Sahara of Niger, in what was a terrestrial area called Jenguebi. “When you want to find something really, truly new, you have to go where few have been or maybe nobody has been,” Sereno says. “In the case of Jenguebi, I don’t think it’s seen a paleontologist before.” His team managed to find the site, led by local Tuareg guides after driving for over a day and half through the desert. “We had a team of nearly 100, including paleontologists, filmmakers, guides, and 64 armed guards. You feel like you’re in an Indiana Jones movie,” Sereno recalls. But the effort paid off.

Back in the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, the Jenguebi was an inland basin laced with rivers—a riparian habitat situated between 500 and 1,000 kilometers away from the nearest marine shoreline. In these riverbank sediments, Sereno and his team unearthed multiple specimens of the new Spinosaurus species they called S. mirabilis. The skeletons were buried right alongside massive, long-necked dinosaurs, including various species of titanosaurian and rebbachisaurid sauropods. To Sereno, the proximity of these bones left no doubt that the animals they belonged to lived and died together in the same inland freshwater environment. And this inland existence drives a pretty big nail in the coffin of the aquatic diver idea.

Prehistoric heron

The researchers point out that all large-bodied secondarily aquatic tetrapods like whales, mosasaurs, or plesiosaurs, are marine. Finding a giant Spinosaurus thriving in an inland river system strongly supports the idea that it was a semiaquatic, shoreline ambush predator that would wade into shallow waters like a giant crane or heron. But there were other hints that the Spinosaurus was not a diver.

“When you calculate this animal’s lung volume and the air that was permanently in its bones, you’ll find out it was buoyant,” Sereno explains. The permanent air sacks in the bones, an anatomical feature shared by many modern birds, most likely kept the Spinosaurus afloat even when it exhaled all the air out of its lungs. “Birds that dive get rid of those air sacks—penguins got rid of them,” Sereno says. “It’s a balloon you can’t fight against.” He added that even its limbs were far too long to be effectively used as paddles.

This wading lifestyle, the team argues in the paper, was not something unique to the S. mirabilis but extended to other Spinosaurus species as well—the skeletal features of the newly discovered S. mirabilis were found fundamentally similar to its shoreline cousins like S. aegyptiacus on which the Jurassic World Rebirth vision was largely based. Sereno argues it's highly unlikely that one was a wading river monster while the other was a deep-diving pursuit predator with limited land mobility.

But there was one thing that made S. mirabilis different from S. aegyptiacus. The word “mirabilis” in the newly discovered Spinosaurus’ name translates to “astonishing” in Latin. What Sereno’s team found so astonishing was the prominent crest atop the animal’s head, one of the largest we’ve ever discovered.

The scimitar crown

Instead of the bumpy, fluted ridge seen on S. aegyptiacus, S. mirabilis sported a blade-shaped, scimitar-like bony crest that arched upward and backward from its snout, reaching an apex high over its eyes. This structure was composed of solid bone, unlike the highly porous, pneumatic casques found on some modern birds. However, the bone itself was etched with fine longitudinal striations and deep grooves, indicating that the bony core was just the foundation.

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

UChicago Fossil Lab

In a living S. mirabilis, this crest would have been enveloped and substantially extended by a keratinous sheath, much like the vibrant growth developed by modern helmeted guinea fowls. If scaled up to a fully mature adult, the bony core alone would measure around 40 centimeters in length; with its keratinous sheath, it could have easily exceeded half a meter. For Sereno, the purpose of this “astonishing” scimitar crown was similar to crests worn today by cranes and herons. “It was asymmetrical. It varied between individuals. So, I think it was solely for display,” Sereno explains.

His team hypothesizes that visual signaling was the primary function of both the cranial crests and the massive trunk and tail sails that define spinosaurids. In the crowded shoreline and riverbank habitats, a towering, brightly colored crest or sail would be an excellent way to broadcast your size, maturity, and genetic fitness to rivals and potential mates without having to engage in a costly physical brawl.

Still, when it came down to it, S. mirabilis, weighing in at well over 7 tons, totally could brawl. “The Spinosaurus was enormous. I think it could have eaten anything it wanted even though its mainstay was fish,” Sereno says.

Crocodile jaw

The showpiece on its forehead aside, the S. mirabilis was a highly specialized killing machine. Its snout featured a low profile with parallel dorsal and ventral margins, terminating in a mushroom-shaped expansion at the tip. The upper and lower jaws allowed the teeth to interdigitate perfectly—there was a notable diastema, a gap in the upper row of teeth, that neatly accommodated the large teeth of the lower jaw. The S. mirabilis jaw structure appears similar to that of modern long-snouted crocodiles, optimized for snatching and snaring aquatic prey with a rapid, trap-like closure. Surprisingly, S. mirabilis showed greater spacing between the teeth in the posterior half of its snout compared to S. aegyptiacus despite being otherwise nearly identical.

Analysis of the animals' overall body proportions led Sereno and his colleagues to suspect these dinosaurs resided in the functional middle ground between semiaquatic waders like herons and aquatic divers like darters, placing them in an ecological niche entirely separate from all other predatory theropods. Based on Sereno’s paper, the evolutionary history of the spinosaurids started in the Jurassic, when their ancestors first evolved that distinctive, elongate, fish-snaring skull before splitting into two main lineages: baryonychines and spinosaurines.

Then, during the Early Cretaceous, the spinosaurines enjoyed a golden age, diversifying across the margins of the Tethys Sea, a late Paleozoic ocean situated between the continents of Gondwana and Laurasia, to become the dominant predators in their respective ecosystems. What most likely brought an end to their reign was climate change.

The end of the line

The final chapter in the Spinosaurus history played out just before the Late Cretaceous, as the Atlantic Ocean was opening up. This is when spinosaurines, limited geographically to what today is Northern Africa and South America, pushed their biological limits, attaining their maximum body sizes as highly specialized shallow-water ambush hunters. This specialization, though, probably led to their extinction.

Around 95 million years ago, at the end of the Cenomanian stage, the world started to shift. An abrupt rise in global sea levels driven by climate changes drowned the low-lying continental basins and created the Trans-Saharan seaway. The complex, shallow river systems and coastal swamps that supported giant wading spinosaurines vanished beneath the waves. “We don’t see spinosaurid fossil records beyond this period,” Sereno explains. The spinosaurid lineage, unable to dive and adapt to more aquatic lifestyles, was brought to an end.

But we still don’t know much about its beginning. “This is going to be the subject of our next paper—where did the Spinosaurus come from?” Sereno says.

Sereno’s paper on the S. mirabilis is published in Science: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adx5486

Read full article

Comments

Fast-charging is actually fast now.

Credit:

Jonathan Gitlin

Fast-charging is actually fast now.

Credit:

Jonathan Gitlin

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

The newly discovered skull, along with a model of what its spike might have looked like on a living animal.

Credit:

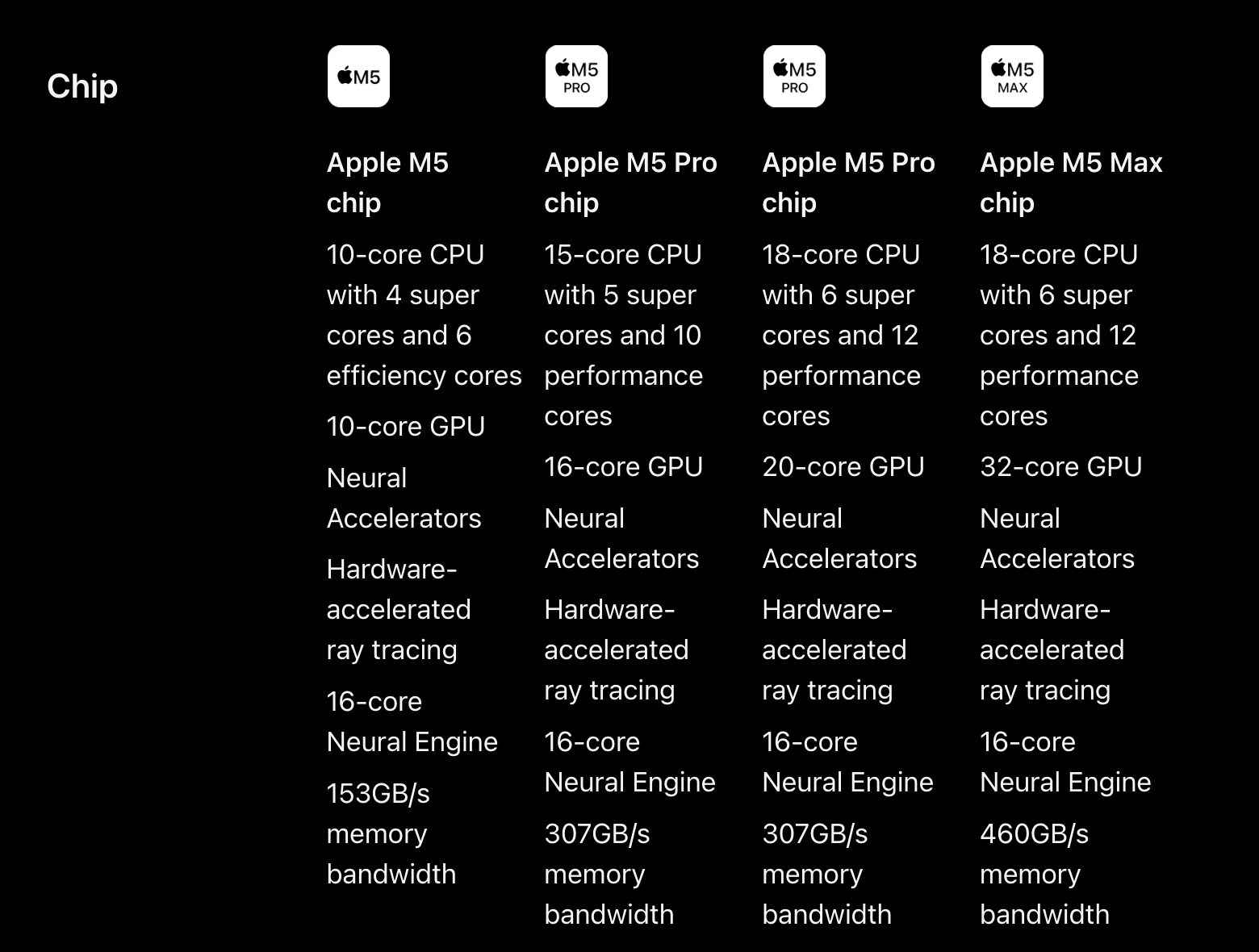

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple

Apple's spec sheets now list three distinct types of CPU cores: "super" cores, performance cores, and efficiency cores.

Credit:

Apple